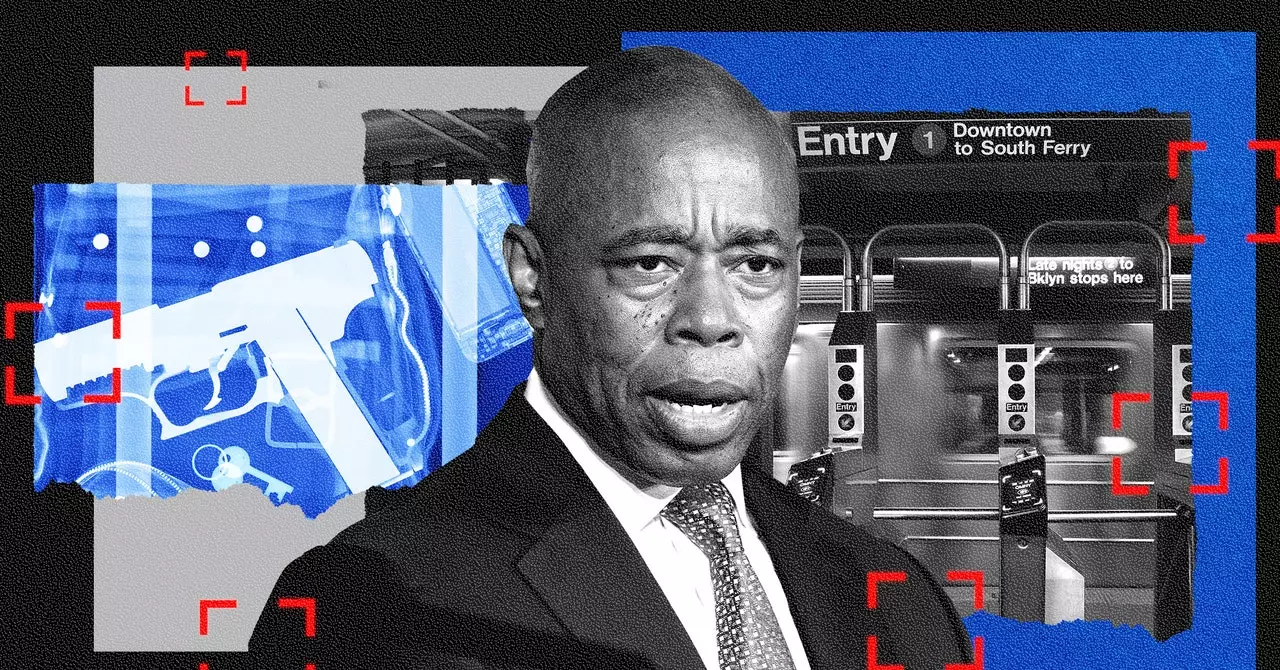

The relationship between Evolv, a technology company specializing in security scanning systems, and former members of the NYPD has raised eyebrows and concerns. It has been revealed that there is a significant overlap between the two entities, with several key individuals having connections to both Evolv and the police force. This includes individuals like Adams and Banks, who rose through the ranks together as police officers. Additionally, Dominick D’Orazio, who formerly held a high-ranking position at Evolv, also had ties to NYPD as a commander in Brooklyn South. Such close connections between a private company and a law enforcement agency raise questions about potential conflicts of interest and favoritism.

Evolv’s CEO, George, has openly acknowledged the company’s ties to the NYPD as a marketing strategy. He boasted about having former police officers as part of the sales team, emphasizing their ability to connect with potential clients in law enforcement. This tactic of highlighting the company’s insider knowledge and relationships within the police force has been used to gain a competitive edge in the market. Moreover, the presence of individuals like David Cohen, a former NYPD deputy commissioner of intelligence, on Evolv’s Security Advisory Board further blurs the lines between the public and private sectors.

Despite the efforts to promote Evolv’s technology, civil rights and technology experts remain skeptical about its effectiveness, especially when proposed for use in subway stations. Critics argue that deploying Evolv’s scanners in such a vast and complex environment is impractical and unlikely to yield meaningful results. Albert Fox Cahn, founder of a privacy advocacy organization, dismisses the idea as “Mickey Mouse public safety” and emphasizes that such measures are inadequate for a transit system as massive as NYC’s subway. The concerns raised by experts highlight the need for a more comprehensive and nuanced approach to public safety.

The prospect of implementing Evolv’s technology in subway stations also raises significant privacy and security concerns. The sheer scale of the NYC subway system, with its 472 stations and 3.6 million daily riders, presents logistical challenges in terms of monitoring and surveillance. Sarah Kaufman, director of New York University’s Rudin Center for Transportation, points out that achieving effective coverage would require extensive monitoring at every entrance, potentially leading to invasive and inconvenient searches for passengers. The reliance on police officers to carry out inspections further complicates the situation, as evidenced by the vague and unspecified guidelines outlined in the draft policy posted by the NYPD.

Evolv’s track record in school deployments does little to inspire confidence in its capabilities. Despite claims of success, instances where the scanners failed to detect weapons and guns have been documented. Internal emails from a school district using Evolv’s technology revealed instances where everyday objects were mistaken for potential threats. This lack of accuracy and reliability in detecting dangerous items further calls into question the suitability of Evolv’s technology for high-stakes environments like schools and public transit systems. The need for thorough testing and evaluation before widespread implementation cannot be overstated.

The questionable connections between Evolv and the NYPD, coupled with doubts about the technology’s efficacy and concerns about privacy and security, raise significant red flags regarding the proposed deployment of Evolv technology in public spaces. It is crucial for decision-makers to prioritize transparency, accountability, and the protection of civil liberties when considering the adoption of security measures that have far-reaching implications for the community. Only through rigorous scrutiny and comprehensive evaluation can we ensure that public safety initiatives are truly effective and beneficial for all.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.